Research Article

André Luciano Lópes

André Luciano Lópes

School

of Pharmacy, Federal University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: andrelucianolopes86@gmail.com

Jorge Andrés García Suárez

Jorge Andrés García Suárez

School of Pharmacy, Federal

University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: jorge.garcia@aluno.ufop.edu.br

Marcos Adriano Carlos Batista

Marcos Adriano Carlos Batista

School of Pharmacy, Federal

University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: marcos.carlos@aluno.ufop.edu.br

Gustavo Henrique Bianco De Souza

Gustavo Henrique Bianco De Souza

School of Pharmacy, Federal University

of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: guhbs@ufop.edu.br

Carla Speroni Ceron

Carla Speroni Ceron

Department of Biological Science,

Federal University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: carla.ceron@ufop.edu.br

Gisele Rodrigues Da Silva

Gisele Rodrigues Da Silva

School of Pharmacy, Federal

University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: giselersilva@ufop.edu.br

Leonardo Máximo Cardoso

Leonardo Máximo Cardoso

Department of Biological Science,

Federal University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: leonardo.cardoso@ufop.edu.br

E-mail: leonardo.cardoso@ufop.edu.br

Sandra Aparecida Lima De Moura*

Sandra Aparecida Lima De Moura*

Corresponding

Author

Department of Environmental Engineering,

Federal University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

E-mail: sandramoura@ufop.edu.br, Tel: +(31) 3559-1073

Received: 2025-10-23 | Revised:2025-11-21 | Accepted: 2025-11-23 | Published: 2025-12-10

Pages: 181-189

DOI: https://doi.org/10.56717/jpp.2025.v04i02.047

Abstract

High

sodium intake can disrupt the tissue sodium balance and inflammatory responses,

potentially impairing wound healing. Natural plant extracts may facilitate

tissue repair by modulating inflammation, however, their therapeutic potential

remains underexplored. This study evaluated the impact of a high sodium

diet (HSD) on cutaneous inflammation induced by subcutaneously implanted

non-biocompatible sponges and

evaluated the anti-inflammatory potential of Baccharis dracunculifolia

(DC) extract formulated in a nanoemulsion (nDC). Weaned male Wistar

rats were fed either a high sodium diet

(HSD; 0.90% Na⁺, w/w) or a standard-sodium diet (SSD;

0.27% Na⁺, w/w) for 12 weeks (n = 16 per group). Sponges were then implanted,

and the animals received oral treatment with 50 mg/kg nDC or vehicle (unloaded

nanoemulsion) once daily for 14 days while continuing their respective diets.

After treatment, sponges were collected for evaluation of cellular

infiltration, vessel density, myeloperoxidase (MPO) and

N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) activities, and histopathology. No

significant differences in inflammatory cell counts, vessel density, or MPO and

NAG activities were observed between the HSD and SSD animals under any

treatment condition (p > 0.05). Histology revealed dense inflammatory infiltrates in

all groups. These findings indicate that HSD did not exacerbate inflammation in

all groups. These results indicate that HSD did not

exacerbate inflammation in this model, and nDC treatment did not modulate

inflammatory responses. In conclusion, neither HSD nor nDC influenced

inflammatory cell recruitment in the murine wound healing model.

Abstract Keywords

Baccharis dracunculifolia, Baccharis dracunculifolia-loaded

nanoemulsion, high sodium diet, cutaneous wound healing model, inflammatory process,

tissue repair.

1. Introduction

High sodium intake has been shown to increase non-osmotic sodium storage in the skin and muscles of both, humans and rodents [1-3]. Elevated extracellular sodium concentration can modulate both, the innate and adaptive immune systems, and includes the activation of cells like macrophages and dendritic cells [2-4]. These mechanisms involve the activation of signaling pathways like NF-κB, MAPK and Nfat5, following sodium influx through epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) on the surface of immune cells [5, 6]. In addition, exposure of human monocytes to elevated Na+ ex vivo caused a coordinated response involving IsoLG-adduct formation, acquisition of dendritic cell-like morphology, and CD83 and CD16 expression [7]. On the other hand, studies have shown that neutrophils are negatively impacted by increased sodium concentrations which compromises neutrophil viability [8]. Sodium can also drive the increase in the production of pro-inflammatory molecules like tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-a), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1b [7], which are critical molecules involved in the early phase regulation of the wound healing process [9]. In addition, NADPH-oxidase inhibition attenuated monocyte activation and IsoLG-adduct formation [7], suggesting the oxidative signaling involvement. Together, these mechanisms show that excessive sodium intake can intensify inflammatory responses across multiple immune cell types, offering a biological explanation for how high sodium exposure may interfere with the normal resolution of inflammation and contribute to impaired wound healing.

The wound healing process can be evaluated through multiple experimental models [10]. Among these, the sponge implantation model represents a particularly robust methodology [11, 12]. This technique involves subcutaneously or intraperitoneally implanting a polyether polyurethane sponge in animals, which subsequently induces localized inflammatory angiogenesis along with the recruitment, accumulation, and proliferation of immune cells [13-15]. Given the established links between high-sodium intake, tissue sodium accumulation, and immune dysregulation, this model provides an ideal platform to investigate how elevated sodium levels affect tissue infiltration and inflammatory responses [16, 17]. Such insights are critical for developing targeted interventions for healing impairments associated with skin sodium imbalance.

The development of innovative therapeutic strategies increasingly combines bioactive compounds derived from natural sources with advanced nanotechnology platforms designed to enhance their delivery, bioavailability, and efficacy. Baccharis dracunculifolia, a plant of the Asteraceae family, has been extensively studied for its potent anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties [18,19]. These pharmacological effects position B. dracunculifolia as a promising candidate for systemic therapies aimed at mitigating tissue damage and promoting tissue remodeling. In this context, nanoemulsion-based delivery systems offer significant advantages by improving the stability, targeted release, and absorption of the plant extracts.

Although sodium intake has been associated with immune modulation, the effects of chronic high sodium consumption on subcutaneous wound inflammation and the potential modulatory role of nanoformulated B. dracunculifolia extract remain insufficiently understood. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of chronic high-sodium intake on tissue inflammation and remodeling using a sponge implantation model, and to assess whether oral administration of a nanoemulsified B. dracunculifolia extract could modulate these local inflammatory responses. This approach not only explores the therapeutic potential of B. dracunculifolia, but also highlights the role of nanotechnology in enhancing natural product–based interventions for inflammatory disorders.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal model and diet

A salt-dependent hypertension model was

employed in this study [20]. Male Wistar rats (35–50 g, 21 days old, weaned) were divided into two

groups (n = 16 for each group): (1) standard-sodium diet (SSD):

received powdered chow containing 0.27% Na⁺ (w/w) (NuviLab, Paulínia,

Brazil); (2) High-sodium diet (HSD): received modified powdered chow with 0.90%

Na⁺ (w/w) (NuviLab, Paulínia, Brazil). Both groups were maintained on

their respective diets for 12 weeks, with ad libitum access to

tap water and food. Environmental conditions were controlled: temperature

(22-24 °C), humidity (40-80%), and a 12 h light/dark cycle. All procedures

adhered to the guidelines of the Brazilian National Council for the Control of

Animal Experiments (CONCEA) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care

and Use Committee (CEUA-UFOP, Protocol 5152120421).

Sterile polyester-polyurethane sponge discs were implanted subcutaneously, following the protocol previously described [16]. The discs measured 8 mm in diameter, 5 mm in thickness, and had an average weight of 4.8 mg. Prior to implantation, the discs were sterilized by immersion in 70°GL ethanol for 48 h. On the day of surgery, the sponges were rinsed thoroughly and boiled in distilled water at 95 °C for 30 min to remove residual ethanol. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (7 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally. The dorsal-lumbar region was aseptically prepared with 70°GL ethanol, and a 1 cm skin incision was made. A subcutaneous pocket was created approximately 2 cm from the incision site, and the sponge disc was inserted. The incision was then sutured, and the animals were housed individually with ad libitum access to tap water and their respective diets. Animals were monitored daily after surgery to evaluate their overall health and identify any indications of infection or distress. Those exhibiting postoperative complications, such as illness or infection, were removed from the study.

Leaves of B. dracunculifolia (DC) were collected from a cultivation field located on the property of the mining company Samarco S.A., Mariana, MG, Brazil (-20.210833, -43.482222). The collection took place during the summer season, between 7:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. Fresh leaves were stored in plastic bags and transported to the laboratory, where they were selected, washed with purified water, and weighed within a few hours of harvesting. The weighed leaves were immersed in 96% analytical grade ethanol at a ratio of 1:1.5 (w/v) and macerated for 10 days at room temperature, protected from light. The maceration process was repeated twice with fresh solvent to ensure exhaustive extraction. The combined liquid fractions were mixed, and ethanol was removed using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure (86 mBar) at 40 °C [20], yielding 5.23 g (9.3%, w/w yield) of crude extract. The resulting crude extract was used for quantitative phytochemical determination as well as for the preparation of the nanoemulsion (nDC) [22].

Phenolic content was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method [23] and flavonoid content was measured using the aluminum chloride colorimetric assay [24]. Gallic acid was used the standard for the phenolic calibration curve, and total phenolic content was expressed as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per milligram of extract. Quercetin and rutin were used as standards for the flavonoid calibration curves, with flavonoid content expressed as micrograms of quercetin equivalents (QE) or rutin equivalents (RE) per milligram of extract (w/w).

A nanoemulsion containing B. dracunculifolia extract (nDC) was prepared as previously described [22]. The formulation was developed so that approximately 1 mL of nDC corresponded to a dose equivalent to 50 mg/kg of the extract, as this dosage was reported as safe for rats [19]. A placebo nanoemulsion, containing all excipients but without the extract, was also prepared and used as the control vehicle. The placebo and nDC were characterized by measuring the particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) using photon correlation spectroscopy with a Malvern Zetasizer ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK).

Animals were divided into four groups (n = 8 for each group): SSD + vehicle, SSD + nDC, HSD + vehicle, and HSD + nDC. The nDC or vehicle was administered orally at a dose of 50 mg/kg in a volume of approximately 1 mL, once every 24 h, for 14 days following sponge implantation. At the end of the treatment period, the animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of a lethal dose of ketamine (300 mg/kg) and xylazine (21 mg/kg). The implanted sponges were collected; weighted, and stored at –20 °C until further analysis.

Tissue infiltration within the implanted sponges was assessed by microscopic examination of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sponge sections. To evaluate the effects of the treatments on the kidneys and liver, samples of these organs were collected from all animals, including both the SSD and HSD groups, treated with either nDC or vehicle. Sponges were excised, fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 4 µm thick slices. The sections were stained with H&E following standard protocols. Microphotographs were captured (10× and 40× magnification) and analyzed to assess the general cytological and histological features.

2.9. Determination of total cells and total vessels in the sponges

For the quantitative analysis of inflammatory infiltrates, the total number of cells within the sponges was counted. Cell counts were performed on 20 randomly selected microscopic fields per group using ImageJ software (version 1.4.3.67). Results were expressed as the mean number of cells ± SD for each group. For vessel quantification, the number of blood vessels was counted in 40 randomly selected fields per group using the same ImageJ software. The mean number of vessels per field was calculated, recorded, and analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5.0. Results were expressed as the mean number of vessels ± SD for each group.

2.10. Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± SD and were evaluated with one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Tukey test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant (p < 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

The bioactive compounds present in B. dracunculifolia, particularly flavonoids and phenolic constituents, have been well documented for their significant anti-inflammatory properties [18, 19]. The DC extract used for the preparation of nDC contained 4.37% (w/w) total phenolic compounds (GAE), 1.82% (w/w) flavonoids (QE), and 6.84% (w/w) flavonoids (RE) (Table 1), suggesting the presence of compounds with potential anti-inflammatory effects.

Table 1. Quantification of phenolic compounds and flavonoids in Baccharis dracunculifolia extract.

Compound | Extract (µg/mg) | Percent (w/w) |

Phenolic compounds (GAE) | 43.7 | 4.37 |

Flavonoids (QE) | 18.2 | 1.82 |

Flavonoids (RE) | 68.4 | 6.84 |

Phenolic content is expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE), and flavonoids are expressed as quercetin equivalents (QE) and rutin equivalents (RE). Values are reported in µg/mg of extract and % (w/w). | ||

Animals were fed either a HSD (0.90% Na⁺, w/w) or a SSD (0.27% Na⁺, w/w) for 12 weeks (n = 16 per group). Sponges were then implanted, and the animals received oral treatment with 50 mg/kg nDC or vehicle (unloaded nanoemulsion) once daily for 14 days while continuing their respective diets. The experiments were conducted using 50 mg/kg nDC, as this dose had been previously evaluated by Batista et al. [21], who reported no adverse or toxic effects in rats, thereby confirming its safety. After treatment, the sponges were carefully collected and weighed. Our results show that sponge weight was not significantly affected by HSD in vehicle-treated animals compared to those on SSD (Fig. 1C, p > 0.05). Similarly, treatment of HSD animals with 50 mg/kg nDC did not significantly alter sponge weight compared to SSD animals receiving nDC (Fig. 1C, p > 0.05). These data suggest that HSD did not increase cellular infiltration within the implanted sponges, as indicated by the lack of difference in sponge weight compared to SSD vehicle-treated animals. Additionally, treatment with nDC did ineffective sponge weight in either dietary group, suggesting that the nanosystem was not effective in modulating cell migration into the sponges.

Figure 1. Photographs of the sponge before (A) and after (B) implantation into the subcutaneous tissue of mice, representative of both HSD- and SSD-fed animals. Weight of sponges measured after 14 days of implantation in rats fed either a standard-sodium diet (SSD - 0.27% Na⁺) or a high-sodium diet (HSD - 0.9% Na⁺), treated with Baccharis dracunculifolia (DC) nanoemulsion (nDC, 50 mg/kg) or vehicle (C). Data are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA; no significant differences were observed (p > 0.05).

Both N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activities are reliable indicators of immune cell infiltration in tissues. NAG, a lysosomal enzyme released primarily by macrophages and neutrophils during inflammation, is widely used to quantify macrophage infiltration at wound sites. MPO, which is predominantly expressed in neutrophils, is a well-established marker of neutrophil infiltration in inflamed tissues [27]. Moreover, decreased MPO activity has been correlated with reduced polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) infiltration and attenuated tissue damage [28]. Thus, measuring NAG and MPO activities provides valuable insights into the extent of macrophage and neutrophil recruitment, respectively, as well as the overall inflammatory status and tissue injury.

MPO and NAG activities were quantified in the sponge implant samples from each animal. MPO activity was not significantly modified by the HSD, as vehicle-treated HSD animals exhibited values comparable to those maintained on the SSD (SSD + vehicle: 0.013 ± 0.003 optical density (O.D.)/mg sponge vs. HSD + vehicle: 0.011 ± 0.003 O.D./mg sponge; Fig. 2A, p > 0.05). Likewise, administration of nDC (50 mg/kg) did not significantly influence MPO activity in HSD-fed rats compared to SSD-fed rats receiving nDC (SSD + nDC: 0.010 ± 0.001 O.D./mg sponge vs. HSD + nDC: 0.007 ± 0.001 O.D./mg sponge; Fig. 2A; p > 0.05).

Consistent with the MPO findings, NAG activity was not significantly affected by HSD in vehicle-treated animals compared to those maintained on the SSD (SSD + vehicle: 0.024 ± 0.003 O.D./mg sponge vs. HSD + vehicle: 0.033 ± 0.003 O.D./mg sponge; Fig. 2B; p > 0.05). Furthermore, nDC treatment (50 mg/kg) did not significantly alter NAG activity in rats fed an HSD or SSD (SSD + nDC: 0.031 ± 0.002 O.D./mg tissue vs. HSD + nDC: 0.029 ± 0.006 O.D./mg tissue; Fig. 2B; p > 0.05).

Figure 2. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) (A) and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) (B) activities measured in sponge sample after 14 days of implantation in animals fed a standard-sodium diet (SSD - 0.27% Na⁺) or a high-sodium diet (HSD - 0.9% Na⁺), treated with B. dracunculifolia (DC) nanoemulsion (nDC, 50 mg/kg) or vehicle. Data are presented as mean ± SD and were analysed by two-way ANOVA; no significant differences were observed (p > 0.05). O.D. – Optic Density.

Therefore, within this murine wound-healing model, neither HSD nor nDC treatment influenced the recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils compared to the control conditions. Additionally, the nanoemulsion formulation failed to produce measurable anti-inflammatory effects in the sponge implantation model under the tested conditions, suggesting that oral administration may have limited the systemic delivery of the extract’s active compounds. Finally, a single dose of nDC may have been insufficient to achieve the desired therapeutic effect.

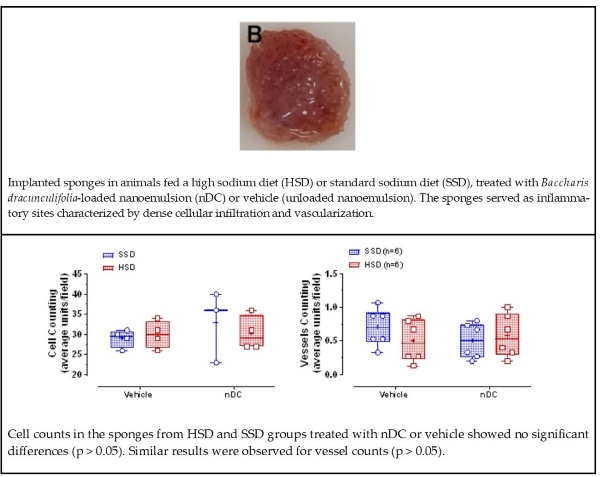

Macrophages and neutrophils, along with other components of the inflammatory infiltrate, were also present in the histopathological images of the sponges. From the SSD and HSD groups, the sponges showed a fibrovascular stroma characterized by abundant thick collagen fibers randomly arranged around the sponge trabeculae, likely as an attempt to isolate the remaining sponge matrix areas [29] (Fig. 3 A-D). Intense cellular infiltration was observed, predominantly composed of mononuclear cells (Fig. 3. A-D inset). Quantitative cell counting showed no significant differences in cellular infiltration between the SSD and HSD groups, nor did nDC treatment alter cell numbers (Fig. 3E) (p > 0.05).

In addition, the sponge matrix was well vascularized, with blood vessels of varying calibers distributed mainly in the peripheral regions of the implants and the around cellular clusters (Fig. 3F). The quantitative analysis of vessel counts revealed that neither HSD nor nDC treatment significantly influenced angiogenesis within the sponge matrix (p > 0.05).

Figure 3. Histological sections of sponges stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), implanted for 14 days in rats fed a standard-sodium diet (SSD - 0.27% Na⁺) or a high-sodium diet (HSD - 0.9% Na⁺), treated with vehicle or Baccharis dracunculifolia nanoemulsion (nDC, 50 mg/kg). All groups exhibited a fibrovascular stroma with abundant collagen fibers (A–D, 10×). An intense inflammatory infiltrate was observed (A–D, inset, 40×). The mean infiltrating cell count (E) and mean vessel density (F) revealed no significant differences between groups, indicating that neither HSD nor nDC treatment affected cellular infiltration or angiogenesis (p > 0.05). Sponge trabeculae, vessels, and macrophages are indicated by “T”, “VS,” and “M", respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

According to Almeida-Junior et al. [30], baccharin - an isolated phenolic compound derived from B. dracunculifolia exhibits a broad spectrum of biological activities, including anti-inflammatory effects potentially linked to antiedematogenic properties, inhibition of polymorphonuclear cell migration, and modulation of NF-κB expression. However, despite the presence of phenolic compounds and flavonoids in the nanoemulsion, these bioactives did not exert the expected therapeutic effects in our model, suggesting that their concentrations within the formulation and/or the dose of the formulation were insufficient to downregulate the established inflammatory response in the implanted sponges under both dietary conditions.

4. Conclusions

The HSD did not exacerbate the inflammatory response in the implanted sponges, as demonstrated by similar cell counts, vessel density, MPO and NAG activity levels compared to animals fed a SSD in the subcutaneous wound healing model. Furthermore, treatment with nDC failed to modulate the inflammatory response in sponges from animals on either diet. These findings suggest that optimization the nanoemulsion formulation is necessary, potentially through dose adjustment and/or enhanced encapsulation efficiency of the phenolic compounds and flavonoids from B. dracunculifolia, to achieve the desired anti-inflammatory effects in this model.

Disclaimer (artificial intelligence)

Author(s) hereby state that no generative AI tools such as Large Language Models (ChatGPT, Copilot, etc.) and text-to-image generators were utilized in the preparation or editing of this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.C., S.A.L.M.; data curation, A.L.L.; methodology, investigation, formal analysis, A.L.L., J.A.G., M.A.B., G.H.B.S.; Supervision, C.S.C., L.M.C., S.A.L.M.; funding acquisition, G.R.S., L.M.C., S.A.L.M.; writing–original draft, A.L.L.; writing – review & editing, G.R.S., L.M.C., S.A.L.M.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the UFOP Multiuser Laboratory 1 of the Graduate Program in Pharmaceutical Sciences (CiPharma) for the analyses performed.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil) under grants no. 304105/2024-4, 402092/2022-8, 309559/2021-9, and 302076/2022‐0 also by the Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG, Brazil) through grants no. APQ-00182-22 and APQ‐00946‐23.

Availability of data and materials

All data will be made available on request according to the journal policy.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. | Thowsen, I.M.; Karlsen, T.V.; Nikpey, E.; Haslene-Hox, H.; Skogstrand, T.; Randolph, G.J.; Zinselmeyer, B.H.; Tenstad, O.; Wiig, H. Na⁺ is shifted from the extracellular to the intracellular compartment and is not inactivated by glycosaminoglycans during high salt conditions in rats. J. Physiol. 2022, 600 (10), 2293–2309. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP282715 |

2. | Titze, J. Sodium Balance Is Not Just a Renal Affair. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. hypertens. 2014, 23 (2), 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mnh.0000441151.55320.c3 |

3. | Titze, J.; Lang, R.; Ilies, C.; Schwind, K.H.; Kirsch, K.A.; Dietsch, P.; et al. Osmotically Inactive Skin Na⁺ Storage in Rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2003, 285(6), F1108–F1117. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00200.2003. |

4. | Kleinewietfeld, M.; Manzel, A.; Titze, J.; Kvakan, H.; Yosef, N.; Linker, R.A.; et al. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature 2013, 496(7446), 518–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11868 |

5. | Chen, Y.; Yu, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W. Role of epithelial sodium channel-related inflammation in Human diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1178410. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1178410 |

6. | Jantsch, J.; Schatz, V.; Friedrich, D.; Schröder, A.; Kopp, C.; Siegert, I.; et al. Cutaneous Na⁺ storage strengthens the antimicrobial barrier function of the skin and boosts macrophage-driven host defense. Cell Metab. 2015, 21(3), 493–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.02.003 |

7. | Barbaro, N. R.; Beusecum, J. V.; Xiao, L.; Carmo, L. d.; Pitzer, A.; Loperena, R.; et al. Sodium activates human monocytes via the nadph oxidase and isolevuglandin formation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 117 (5), 1358–1371. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvaa207 |

8. | Li, X.; Alu, A.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X.; Luo, M. The modulatory effect of high salt on immune cells and related diseases. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55 (9), e13250. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.13250 |

9. | Eming, S. A.; Krieg, T.; Davidson, J. M. Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007, 127 (3), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700701 |

10. | Rafiyan, M.; Sadeghmousavi, S.; Akbarzadeh, M.; Rezaei, N. Experimental animal models of chronic inflammation. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2023, 4, 100063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crimmu.2023.100063 |

11. | Moura, S.A.; Ferreira, M.A.; Andrade, S.P.; Reis, M.L.; Noviello, L.; Cara, D.C. Brazilian green propolis inhibits inflammatory angiogenesis in a murine sponge model. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 182703. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/nep197 |

12. | Tian, Y.; Terkawi, M.A.; Onodera, T.; Alhasan, H.; Matsumae, G.; Takahashi, D.; Masanari, H.; Taku, E.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Hiroaki, K.; et al. Blockade of XCL1/lymphotactin ameliorates severity of periprosthetic osteolysis triggered by polyethylene particles. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1720. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01720 |

13. | Ferreira, M.A.; Barcelos, L.S.; Campos, P.P.; Vasconcelos, A.C.; Teixeira, M.M.; Andrade, S.P. Sponge-induced angiogenesis and inflammation in PAF receptor-deficient mice (PAFR-KO). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 141, 1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0705731 |

14. | Mendes, J.B.; Rocha, M.A.; Araújo, F.A.; Moura, S.A.; Ferreira, M.A.; Andrade, S.P. Differential effects of rolipram on chronic subcutaneous inflammatory angiogenesis and on peritoneal adhesion in mice. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 78, 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mvr.2009.08.008 |

15. | Pereira, N.B.; Campos, P.P.; Oviedo Socarrás, T.; Pimenta, T.S.; Parreiras, P.M.; Silva, S.S.; Kalapothakis, E.; Andrade, S.P.; Moro, L. Sponge implant in swiss mice as a model for studying loxoscelism. Toxicon. 2012, 59, 672–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.02.005 |

16. | De Oliveira, L.G.; Figueiredo, L.A.; Fernandes-Cunha, G.M.; Barcelos, M.M.; Machado, L.A.; Da Silva, G.R.; Lima, S.A. Methotrexate locally released from poly(ε-caprolactone) implants: inhibition of the inflammatory angiogenesis response in a murine sponge model and the absence of systemic toxicity. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 3731–3742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.24569 |

17. | Barcelos, L.S.; Coelho, A.M.; Russo, R.C.; Guabiraba, R.; Souza, A.L.; Bruno-Lima, G., Jr.; Proudfoot, A.E.; Andrade, S.P.; Teixeira, M.M. Role of the chemokines CCL3/MIP-1α and CCL5/RANTES in sponge-induced inflammatory angiogenesis in mice. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 78, 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mvr.2009.04.009 |

18. | Moura, S.A.; Lima, L.D.; Andrade, S.P.; Da Silva Cunha, A., Jr.; Órefice, R.L.; Ayres, E.; Da Silva, G.R. Local drug delivery system: inhibition of inflammatory angiogenesis in a murine sponge model by dexamethasone-loaded polyurethane implants. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 2886–2895. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.22497 |

19. | Figueiredo, S.M.; Nogueira Machado, J.A.; Almeida, M.; Abreu, S.R.; Abreu, J.A.; Filho, S.A.; Binda, N.S.; Caligiorne, R.B. Immunomodulatory properties of green propolis. Recent Pat. Endocr. Metab. Immune Drug Discov. 2014, 8, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.2174/1872214808666140619115319 |

20. | Gomes, P.M.; Sá, R.W.M.; Aguiar, G.L.; Paes, M.H.S.; Alzamora, A.C.; Lima, W.G.; de Oliveira, L.B.; Stocker, S.D.; Antunes, V.R.; Cardoso, L.M. Chronic high-sodium diet intake after weaning leads to neurogenic hypertension in adult Wistar rats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5655. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05984-9 |

21. | Grance, S.R.M.; Teixeira, M.A.; Leite, R.S.; Guimarães, E.B.; de Siqueira, J.M.; de Oliveira Filiu, W.F.; Vieira, M.C. Baccharis trimera: effect on hematological and biochemical parameters and hepatorenal evaluation in pregnant rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.12.020 |

22. | Batista, M.A.C.; Freitas, F.E.D.A.; Braga, D.C.A.; Souza, J.A.; Antunes, V.R.; Souza, G.H.B.; Dos Santos, O.D.H.; Brandão, G.C.; Kohlhoff, M.; Ceron, C.S.; Moura, S.A.L.; Cardoso, L.M. Antihypertensive effect of a nanoemulsion of Baccharis dracunculifolia leaves extract in sodium-dependent hypertensive rats. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2024.2397724 |

23. | Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic–phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.1965.16.3.144 |

24. | Maksimović, Z.; Malencić, D.; Kovacević, N. Polyphenol contents and antioxidant activity of Maydis stigma extracts. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 873–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2004.09.006 |

25. | Almeida, S.A.; Orellano, L.A.; Pereira, L.X.; Viana, C.T.; Campos, P.P.; Andrade, S.P.; Ferreira, M.A. Murine strain differences in inflammatory angiogenesis of internal wound in diabetes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 86, 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.146 |

26. | Huang, H.; Wismeijer, D.; Hunziker, E.B.; Wu, G. The acute inflammatory response to absorbed collagen sponge is not enhanced by BMP-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030498 |

27. | Carollo, M.; Hogaboam, C.M.; Kunkel, S.L.; Delaney, S.; Christie, M.I.; Perretti, M. Analysis of the temporal expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors during experimental granulomatous inflammation: role and expression of MIP-1α and MCP-1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 134, 1166–1179. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0704337 |

28. | Jung, Y.Y.; Nam, Y.; Park,Y.S.; Lee, H.S.; Hong, S.A.; Kim, B.K.; Park, E.S.; Chung, Y.H.; Jeong,J.H. Protective effect of phosphatidylcholine on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation in multiple organ injury. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 17, 209–216. https://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2013.17.3.209 |

29. | Cassini Vieira, P.; Deconte, S.R.; Tomiosso, T.C.; Campos, P.P.; Montenegro, C.F.; Araújo, H.S.S.; Barcelos, L.S.; Andrade, S.P.; Araújo, F. DisBa-01 inhibits angiogenesis, inflammation and fibrogenesis of sponge-induced fibrovascular tissue in mice. Toxicon. 2014, 92, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.10.007 |

30. | Almeida-Junior, S.; de Oliveira, K.R.P.; Marques, L.P.; Martins, J.G.; Ubeda, H.; Santos, M.F.C.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Andrade e Silva, M.L.; Ambrósio, S.R.; Bastos, J.K.; Ross, S.A.; Furtado, R.A. In vivo anti-inflammatory activity of baccharin from Brazilian green propolis. Fitoterapia. 2024, 175, 105975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2024.105975 |

This work is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution

4.0

License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Abstract

High

sodium intake can disrupt the tissue sodium balance and inflammatory responses,

potentially impairing wound healing. Natural plant extracts may facilitate

tissue repair by modulating inflammation, however, their therapeutic potential

remains underexplored. This study evaluated the impact of a high sodium

diet (HSD) on cutaneous inflammation induced by subcutaneously implanted

non-biocompatible sponges and

evaluated the anti-inflammatory potential of Baccharis dracunculifolia

(DC) extract formulated in a nanoemulsion (nDC). Weaned male Wistar

rats were fed either a high sodium diet

(HSD; 0.90% Na⁺, w/w) or a standard-sodium diet (SSD;

0.27% Na⁺, w/w) for 12 weeks (n = 16 per group). Sponges were then implanted,

and the animals received oral treatment with 50 mg/kg nDC or vehicle (unloaded

nanoemulsion) once daily for 14 days while continuing their respective diets.

After treatment, sponges were collected for evaluation of cellular

infiltration, vessel density, myeloperoxidase (MPO) and

N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) activities, and histopathology. No

significant differences in inflammatory cell counts, vessel density, or MPO and

NAG activities were observed between the HSD and SSD animals under any

treatment condition (p > 0.05). Histology revealed dense inflammatory infiltrates in

all groups. These findings indicate that HSD did not exacerbate inflammation in

all groups. These results indicate that HSD did not

exacerbate inflammation in this model, and nDC treatment did not modulate

inflammatory responses. In conclusion, neither HSD nor nDC influenced

inflammatory cell recruitment in the murine wound healing model.

Abstract Keywords

Baccharis dracunculifolia, Baccharis dracunculifolia-loaded

nanoemulsion, high sodium diet, cutaneous wound healing model, inflammatory process,

tissue repair.

This work is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution

4.0

License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Editor-in-Chief

This work is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

License.(CC BY-NC 4.0).